Marching to Their Own Drum: Native American Musicians and the History of the United States Government Boarding School Bands

Vincent Veerbeek is currently a PhD researcher in the Doctoral Program in History and Cultural Heritage at the University of Helsinki, where he is working on a dissertation about marching bands at government boarding schools for Native Americans and musicians who led those bands. He graduated from Radboud University in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, with a BA in American Studies (2018) and an MA in Historical Studies (2020). In 2019, he spent time at the University of California, Riverside to research the history of music at the Sherman Institute boarding school. During the 2023-2024 academic year, he was a Fulbright visiting scholar at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque.

“Love of music is one of the most elevating influences that can be brought to bear upon the human soul, and there can be no doubt that the culture of this humanizing instinct will do much to sustain these avant-couriers of Indian civilization, in the hard struggle against the degenerating influences by which they will be environed after leaving the protecting care of their friends at Chemawa.” (Wells, 1887: 11)

In this quote from 1887 about the marching band of a government boarding school for Native American children in the northwestern United States, magazine editor Henry L. Wells expressed a commonly-held belief at the time: that music was integral to efforts by white Americans to assimilate Indigenous communities. Indeed, instruction in European and American music was a central part of the education program at government-run schools established in the late nineteenth century. Many white officials at the time viewed Native Americans and their place in the United States through a binary lens of civilization and savagery, which they also applied to music. From this perspective, Western music represented the best of civilization, whereas the many different musical traditions of Native American communities were uncivilized and even dangerous (Troutman 2009: 11-13). Moreover, officials believed that Western music was so powerful it could transform the emotions, thoughts, and even identity of a person, especially in children. In reality, however, the role that music played in the effort to erase Indigenous cultures was much more complex. That discrepancy is particularly apparent in the history of school marching bands, which Native Americans used for their own empowerment and expression.

Marching bands were typically the most prominent musical groups at government schools between 1880 and the 1930s, but they represented the goals of the assimilation program as well as its shortcomings. Most significantly, these bands reflected the culture of military discipline that characterized life at the schools (Adams 1995: 117) and seemed to affirm the efficacy of music as a tool for assimilation. However, even as marching bands embodied white attitudes about civilization and Americanness, Native Americans were able to actively shape these institutions within the narrow confines of the boarding school system. To better understand the significance of these boarding school bands, my doctoral dissertation studies the bands that were active at different government schools across the United States from a cultural-historical perspective, and incorporates the stories of young Native Americans who became band directors after their time in school. This article presents part of that research, examining how officials established the first marching bands during the 1880s, what role they played in boarding school life, and the experiences that two individuals had with these bands as both student musicians and bandmasters.

Music in service of assimilation

Following a century of war and territorial expansion, the United States government began implementing social programs in the 1870s as a new strategy for assimilating the Indigenous communities within its borders. Under the pressure of a white elite who wanted to reform government policy in order to more effectively destroy Indigenous cultures and absorb Native Americans into the United States, cultural assimilation became the primary focus of policy (Adams 1995: 8-11; Fear-Segal 2007: xii). Education was of particular importance to this new policy, as the government began an unprecedented effort to raise the next generation of Native Americans according to the norms of mainstream United States society. Although the federal government had financially supported religious organizations to run mission schools as early as 1819 (Reyhner and Eder 2004: 43-44), officials now became more directly involved. Between 1879 and the early 1900s, hundreds of government-run schools opened across the country where Native American children received an education that ostensibly communicated values of self-sufficiency, discipline and patriotism (Adams 1995: 21-27).

The education system that the United States government established at the end of the nineteenth century consisted of three main types of schools: day schools and boarding schools on reservations, and large off-reservation institutions. My research focuses on this latter group of 25 boarding schools (see Figure 1), which were places where children typically lived far away from their families and communities for extended periods of time (Adams 1995: 28-36). In this manner, officials wanted to bring children closer to white communities and create environments where teachers and school staff could immerse young Native Americans in a model version of how they envisioned United States society. The first example of this new approach was the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, which opened at a former military barracks in Pennsylvania on November 1, 1879. Here, military general Richard Henry Pratt developed an education program that would form a model for the other off-reservation boarding schools that opened in subsequent decades.

The Carlisle model of education amounted to a school experience centered around labor and military discipline that led to hardships for many young Native Americans. During the early decades, most schools followed a half-half curriculum that combined classroom work in English and other academic subjects with vocational training in various trades like carpentry and tailoring. Students lived at the schools and life followed a system of military discipline with sound signals, roll calls and marching, as well as punishment for pupils who disobeyed one of the many rules that these schools had (Woolford 2015: 142-143). The emphasis on labor also meant that students were often responsible for the construction and repair of school buildings, mending and washing uniforms, preparing food, and doing other tasks. Because sickness was prevalent in some institutions and nutrition was not always adequate, student deaths were common at Carlisle and elsewhere (Fear-Segal 2007: 232). Even though the boarding school experience was traumatic for many young Native Americans and continues to leave its mark on Indigenous communities to this day, students were able to find respite from those hardships too, for example through music.

Music was a central part of life at all government schools and served as an extension of the education program, but young Native Americans also used music as an opportunity to escape and express themselves. Similar to the views that Henry Wells expressed in his 1887 article, many white officials thought that music could reach the souls of Native American children directly. In her book on the Chemawa boarding school in Oregon, musicologist Melissa Parkhurst summarizes this view as follows: “for civilization to really take hold in Indian communities, the students’ interior lives and emotional allegiances had to be remade” (2014: 12). More than simply replacing Indigenous cultural traditions with non-Indigenous ones, officials believed music education could effect a complete transformation, which often proved to be wishful thinking. More specifically, training in music mattered because to be a good American citizen was to know and appreciate its culture and music (Troutman 2009: 114). Instead of engaging with the songs and dances of their own communities, students therefore learned to sing Christian hymns and patriotic songs, and played a repertoire of European classical music and American standards. Even so, students were able to engage in “clandestine acts of cultural preservations” (Adams 1995: 233) in unsupervised moments, as they found ways to sing and play the music of their own communities in private. Other schools were more lenient toward Indigenous cultural expression, and officials sometimes even gave a stage to students to perform their tribal dances if it suited their own financial interests (Sakiestewa Gilbert 2010: 76-81). Nevertheless, such events were exceptions at a time when instruments like bugles, pianos and organs characterized the sound of daily life at boarding schools.

In addition to a basic classroom education in vocal and sometimes instrumental music, students at off-reservation schools usually had opportunities to play in one of several extracurricular organizations. These typically included choirs, glee clubs, as well as a mandolin and guitar club for female students, and a marching band for male students (Troutman 2009: 117). Similar to other recreational activities like debating or sports, such activities communicated the central values of assimilation policy. Among the various music groups that existed at schools, marching bands were typically the most prominent and prestigious. Nevertheless, despite their importance to school life, few scholars have analyzed their significance in a broader context. Aside from works by John Troutman (2009) and Melissa Parkhurst (2014) and studies on individual school bands (e.g., McAnally 1996; Handel and Humphreys 2005; Veerbeek 2020) music remains an understudied subject in boarding school scholarship. As a result, crucial questions remain unanswered regarding, for example, the early history of boarding school bands, similarities and differences between schools, and how these bands actually affected the lives of young Native Americans. All of this is particularly important considering that school bands were part of the off-reservation school system from the very beginning.

Marching in step with society

Within a year from the opening of the Carlisle Indian School, school officials brought together a group of students who would form the first band. In June of 1880, the school newspaper reported that several students were learning to play the bugle (School News 1 (2): 2) and the school soon received a full set of band instruments through a donation. Although Pratt worked for the United States government and reported directly to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, the government did not provide resources for a band. Instead, a wealthy benefactor from Boston by the name of Eleanor Baker provided the first band instruments. After the instruments arrived at the school, Pratt appointed Clara Coleman, a musician whose husband was a teacher at the school, as band director. On July 15, 1880, twelve male students from seven tribal nations received their first instruction as the newly established school band (Eadle Keatah Toh, 1881: 3). Among them was Lakota student Luther Standing Bear, who later described the events of that day in his memoir:

“The little woman had a black case with her, which she opened. It held a beautiful horn, and when she blew on it it sounded beautiful. Then she motioned to us that we were to blow our horns. Some of the boys tried to blow from the large end. Although we tried our best, we could not produce a sound from them” (Standing Bear 1975: 148).

Although the students were initially puzzled by their instruments, they learned quickly. In fact, the band made enough progress that Pratt let them perform for the whole school on August 16 during an appearance on the bandstand in the middle of the schoolgrounds (School News 1 (4): 2). One of the songs they played during this first concert was “In the sweet by and by,” a popular hymn composed in 1868. In many respects, this first performance in the summer of 1880 set the tone for what the Carlisle band and other boarding school bands would become.

The success of the Carlisle band grew steadily over the following years and as it did, the school established a model that other institutions would soon follow. Throughout the school year, the band practiced daily and in his second annual report, school superintendent Pratt (1881: 190) noted that the marching band had “continued to improve, and the musical ability developed is a matter of astonishment.” Under the leadership of painting instructor Phil Norman, the Carlisle band became a renowned musical institution during the 1880s. In addition to regular concerts on campus, the school band performed on stages along the American East Coast, and participated in parades and marches, including several high-profile events. Among the most notable appearances of the Carlisle band were the opening of the Brooklyn Bridge in 1883, the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago, as well as several presidential inaugurations. Just as significantly, a large number of those achievements occurred under the leadership of Dennison Wheelock, a member of the Oneida Nation who graduated from Carlisle in 1890 and returned to the school two years later to lead the band. He held the position for nearly a decade, during which time he solidified both the reputation of the Carlisle band and his own.

While the Carlisle school band rose to fame, the government established off-reservation schools across the Western United States that followed a similar approach to what Pratt was doing at Carlisle, and placed a similar emphasis on music as well. Indeed, wherever school officials could find the resources, they purchased a set of band instruments and appointed a staff member to lead a marching band. Oftentimes, they too relied on donations or fundraising from employees or the local community to be able to purchase instruments and start their own bands. Likewise, while some schools hired an employee to work exclusively as band director, it was more common that another employee with musical talent would direct a band alongside their work as tailor or wagonmaker for example. Although some schools were more successful in establishing and maintaining a band than others, all off-reservation schools had a marching band for at least part of their history. These bands would practice regularly, in some cases every evening, participate in drills and parades with the student body, and perform both on schoolgrounds and at public events in local communities and further away.

The presence of marching bands at off-reservation schools served a variety of purposes, both internally and externally. Within the school, bands contributed to the culture of military discipline that characterized school life. Parades, roll calls, and flag-raising ceremonies became important rituals of everyday life in which the school band would often play a central role. Moreover, by training a relatively small group of students to play a repertoire of music that communicated certain ideas about civilization and patriotism, school officials were able to ensure that the entire student body heard that music. For the world outside the school walls, bands demonstrated the apparent successes of assimilation to the general public. As Troutman (2009: 123) writes, “Marching with such discipline, playing “civilized” compositions through brass instruments, the bands offered a glimpse of assimilation at its most mechanical and perfect.” Many schools developed a tradition of Sunday concerts that were open to the public, and bands also frequently traveled to fairs, parades and other events. There, audiences could see young Native Americans in uniforms marching in step to patriotic music in a display of their supposed assimilation. Finally, for the students themselves band membership was often a valuable educational experience, a source of prestige with their peers, and a form of escape from the drudgery of everyday life at school. Although being in the band was hard work, student musicians had unique opportunities to travel, visit new places, and experience major events like Fourth of July parades and world’s fairs.

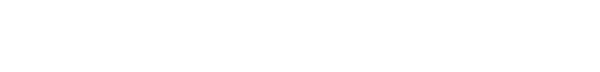

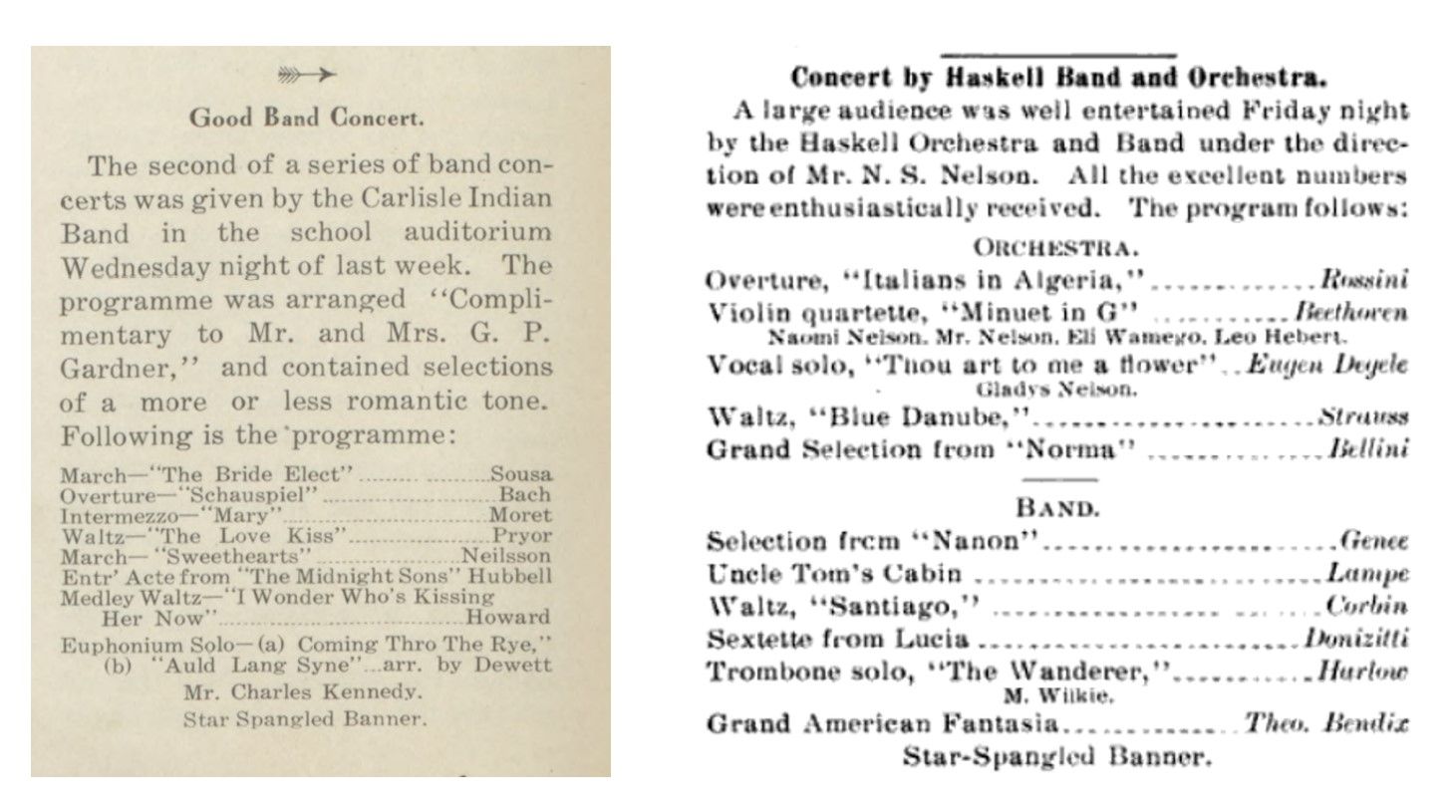

One aspect of the boarding school bands that provides clear evidence of how they represented the assimilation agenda was their repertoire. Although it is unclear who created the first program for a boarding school band or to what extent the schools influenced each other directly, there seems to have been a consensus on what type of music bands should play. In general, it is likely that the bandmaster at a school would be in charge of making those decisions, and in doing so they followed both their personal taste and the taste of the general public, as well as the work of their peers. The concert programs in Figure 3 provide an impression of the typical repertoire that these marching bands would play at the turn of the twentieth century. Even though these programs are from the 1910s, they differ little from the music that bands played two decades earlier or even a decade later. Across the country, young Native Americans attending government schools would typically play a combination of classical pieces by composers like Bach and Beethoven and works by American composers, especially marches by John Philip Sousa and other patriotic tunes. For instance, “The Star-Spangled Banner,” which would become the national anthem of the United States in 1931, was often the closing song. All of these songs together communicated a sense of superiority of white America over Indigenous communities and their cultures, a message to which students certainly did not always listen. Nevertheless, successive generations of Native American students continued to play a similar repertoire well into the 1930s even as marching bands became less dominant in popular culture.

With the growing number of young Native Americans who had received at least part of their musical training playing in a school band, and the increased demand for qualified band directors at new schools, officials often hired former students to lead these bands. In my research, I have so far encountered the stories of over fifty Native American men who attended boarding schools, played in marching bands, and then spent at least part of their careers teaching music to the next generation of Native Americans. Based on these findings, it appears that it was quite common for former students to lead school bands, but their experiences have not become part of the scholarly discourse on boarding schools and their music programs. Even though scholars have researched the experiences of Native Americans who worked as government employees and as teachers (see, e.g., Cahill 2011: 105-111), the experiences of band directors have largely gone overlooked. This oversight is most likely due to the fact that many schools did not list their band directors separately in reports and other records, and if they did, it is not always immediately apparent whether an employee was white or Native American. Even so, this history is worth highlighting because it complicates the narrative of marching bands as a pinnacle of the assimilationist education program. Moreover, band directors had an influential role in the schools, as they were often responsible for maintaining discipline, which makes it significant that so many Native Americans held these positions of relative power.

Assimilation in a different key

Among the Native American musicians who led boarding school bands across the country, there were a significant number of Carlisle graduates, and the school itself would have several Native American bandleaders as well. The first of these was Dennison Wheelock, a member of the Oneida Nation in Wisconsin born in 1874, who graduated from the school in 1890 and became its third band director in 1892. For the better part of a decade, he led the increasingly well-known marching band at countless concerts and parades, and he himself became one of the most famous Native American musicians of his time. In addition to his work as a director, Wheelock was also a prolific composer, writing a march dedicated to Carlisle in 1896, and completing the symphony “Aboriginal Suite” in 1900, which would become his magnum opus. Shortly after he performed this symphony at Carnegie Hall that year, however, a personal tragedy fundamentally changed his life and his career (Hauptmann 2006: 127). Following the death of his young son, Wheelock left Carlisle and worked at various boarding schools – including as bandmaster at Haskell Institute in Kansas for two years – before pursuing a career in law. In 1911, he was also one of the founding members of the Society of American Indians, and he devoted much of his later career to advocating for the rights of Native Americans both in Washington and back home in Wisconsin, all the while continuing to perform as a musician (Hauptmann 2006: 130-131).

Although Wheelock held similar views to Richard Pratt, who was something of a mentor to him, his experiences do not reflect a straightforward process of assimilation into American society. Despite his complicated relationship with the Oneida Nation and estrangement from his own community (Hauptmann 2006: 130-132) he used both his musical career and his work as an advocate and attorney to represent Native American interests and demonstrate what they were capable of. This ambiguity is particularly important in relation to his position as a band director at different boarding schools. As Amelia Katanski (2005: 92) argues, Wheelock may not have defied school officials in that position, but his experiences illustrate that students “were able to assert their own creativity to develop and maintain complex identities.” Having a Native American director did not mean that boarding school bands lost their function as instruments of attempted assimilation, but it did provide young students with a possible vision of their future that was different from the working-class ambitions of the government program.

Some of the young Native Americans who played in the Carlisle school band while Dennison Wheelock was its director later had opportunities to pursue musical careers of their own. One such person was Richard Barrington, a member of the Washoe tribal community, who was born in 1890 and grew up in Truckee, California. After white officials kidnapped him at age 10 and brought him to the newly established Stewart Indian School in Carson City, Nevada, Barrington spent eleven years in the boarding school system before graduating from Stewart in 1901. As part of his education, he traveled east in 1898 to attend the Carlisle Indian School for two years (Thompson 2013: 205). Significantly, his time as a student at Carlisle coincided with the tenure of Dennison Wheelock as band director at the school. Unfortunately, it is unclear from the sources I have had access to so far how well the two men knew each other, or what their relationship was like. Nevertheless, their shared experiences at Carlisle provide one example where two successive generations of boarding school musicians had opportunities to interact. Those interactions provided Barrington with a potential opportunity to learn from Wheelock both as a musician and as a politically engaged Indigenous person.

Whether it was due to his education at Stewart or his experiences playing in the Carlisle band, music would remain an important part of the life and career of Richard Barrington. After graduating, he attended a public high school in Carson for a few years, and then worked in the lumber industry in the area where he had grown up. During this time, he continued to make a name for himself as a musician. Most notably, he organized and led a marching band of Native American musicians that performed during the 1915 World’s Fair in San Francisco. The next year, off-reservation boarding school Sherman Institute in Southern California hired Barrington as a temporary band instructor for six months. During that time, he composed a march for one of the debating clubs at the school, which students performed just before he left the school (Sherman Bulletin, 1917: 2). Subsequently, in March of 1917, the government appointed him to the position of band director at his old school Stewart. Despite initially having attended the school involuntarily, Barrington did apparently look back positively on his time as a student there. The school newspaper even reported that upon his return, Barrington said “it seems like home to get back to his alma mater again” (The Indian Enterprise, 1917: 10). For the next four years, he worked at Stewart as band and orchestra director, as well as clerk and instructor in shoe and harness making.

Ultimately, however, Barrington would have a fairly brief career teaching music to young Native Americans on behalf of the government. After a short period working at a school in Crownpoint, New Mexico, Barrington resigned because he was “disillusioned with the politics of the Indian Service” (Thompson 2013: 206) and no longer wanted to work for the federal government. Details on what led to this decision are scarce, but there was clearly some kind of tension between what he had envisioned his work would be like and the reality of it. Other Native American band directors faced similar challenges (Troutman 2009: 209-217) as well as other obstacles that made relatively long careers like those of Dennison Wheelock uncommon; even though there were exceptions. In fact, some Native American musicians spent decades of their life leading marching bands at one or more institutions.

After Barrington stopped working for the federal government, he returned home to continue his work in the lumber industry, but he never stopped advocating for his community. Overall, the available information on his later years indicates that he lived a life that seemed to conform to the expectations of government officials, as Barrington owned land and started his own business, while his son Lloyd even attended university (Thompson 2013: 206). Despite those outward signs of assimilation, however, Barrington clearly never gave up his Washoe identity, as he also used his position to further Native American interests, and continued to support Native Americans in other ways. He was an active member of his community, gave lectures about the dangers of alcohol, and became involved in land claims. In 1963, for example, Barrington traveled to Washington, DC, to provide testimony in a major case about Washoe land rights (Hittman 2013: 103). In the end, music was one of several skills that Barrington honed during his time in the boarding school system. However, he did not use those skills to disappear into white society, as the government might have hoped, but instead created a modern Washoe and Native American identity for himself, and helped others do the same.

Conclusion

The stories of Dennison Wheelock and Richard Barrington provide a small glimpse into the multitude of experiences that young Native Americans had at government schools both as students and as professional musicians. These types of stories complicate the narrative about boarding school bands and their legacy, which is why they deserve more attention than they have received thus far. Much of what survives about the early history of the marching bands are photographs, concert programs and official accounts, which on the surface seem to represent signs of assimilation, however involuntary. Even as young Native Americans marched to Western music while wearing military-style uniforms, however, they maintained their own identities as citizens of many different tribal nations, and began to form new identities both as Indigenous people and as Americans.

In short, an in-depth examination of the marching bands that existed at off-reservation schools leads to new insights about the complicated realities of identity formation through music in the context of an education program focused on assimilation. By taking charge of these bands, Native American musicians helped shape boarding schools, and added a new dimension to the education program that was beyond the control of white officials. Even within the confines of the boarding school program, these individuals found opportunities to change the narrative and presented the next generation of Native Americans with different possibilities for their future as members of specific communities, as Indigenous people more generally, and as American citizens. As Native Americans made band music their own, their marching bands survived well past the closing of the last assimilationist schools. Indeed, there are Native American communities across the United States where the marching band tradition lives on today in organizations like the Iroquois Indian Marching Band and the Fort Mojave Tribal Band.

Primary sources

“Campus Briefs.” March 7, 1917. The Sherman Bulletin 9 (10): 2. Sherman Indian Museum.

“Campus Chronicle.” March, 1917. The Indian Enterprise 1 (7): 10. Stewart Indian School Cultural Center and Museum.

“Concert by Haskell Band and Orchestra.” March 15, 1918. Indian Leader 21 (28): 3.

“Good Band Concert.” February 11, 1910. The Carlisle Arrow 6 (23): 2. Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center.

“Our School.” March, 1881. Eadle Keatah Toh 1 (9): 3. Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center.

Pratt, Richard Henry 1881. “Report of School at Carlisle.” In: Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior for the year 1881, 184-191. Washington: Government Printing Office.

Untitled. June, 1880. School News 1 (2): 2. Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center.

Untitled. September, 1880. School News 1 (4): 2. Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center.

Wells, Henry L. January 1887. “The Indian School at Chemawa.” The West Shore 13 (1): 5-12.

Secondary sources

Adams, David Wallace 1995. Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience, 1875-1928. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

Cahill, Cathleen 2011. Federal Fathers and Mothers: A Social History of the United States Indian Service, 1869-1933. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Fear-Segal, Jacqueline 2007. White Man’s Club: Schools, Race, and the Struggle of Indian Acculturation. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Handel, Greg, and Jere Humphreys 2005. “The Phoenix Indian School Band, 1894–1930,” Journal of Historical Research in Music Education 16 (2): 144-161.

Hauptman, Laurence M 2006. “From Carlisle to Carnegie Hall: The Musical Career of Dennison Wheelock.” In: The Oneida Indians in the Age of Allotment, 1860-1920, eds. Laurence M. Hauptman and L. Gordon McLester III: 112-138.

Hittman, Michael 2013. Great Basin Indians: An Encyclopedic History. Reno and Las Vegas: University of Nevada Press.

Katanski, Amelia 2005. Learning to Write “Indian.” The Boarding-School Experience and American Indian Literature. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

McAnally, J. Kent 1996. “The Haskell (Institute) Indian Band in 1904: The World’s Fair and Beyond.” Journal of Band Research 31 (2): 1-34.

Parkhurst, Melissa 2014. To Win the Indian Heart: Music at Chemawa Indian School. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press.

Reyhner, Jon, and Jeanne Eder 2004. American Indian Education: A History. University of Oklahoma Press.

Sakiestewa Gilbert, Matthew 2010. Education Beyond the Mesas: Hopi Students at Sherman Institute, 1902-1929. Lincoln: University Press of Nebraska.

Standing Bear, Luther. 1928. My People the Sioux. Ed. Earl Alonzo Brininstool. Reprint, 1975. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Thompson, Bonnie 2013. “The Student Body: A History of the Stewart Indian School, 1890-1940.” PhD dissertation, Arizona State University.

Troutman, John W 2009. Indian Blues: American Indians and the Politics of Music, 1879-1934. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Veerbeek, Vincent 2020. “A Dissonant Education: Marching Bands and Indigenous Musical Traditions at Sherman Institute, 1901–1940.” American Indian Culture and Research Journal 44 (4): 41-57.

Woolford, Andrew 2015. This Benevolent Experiment: Indigenous Boarding Schools, Genocide, and Redress in Canada and the United States. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba.